Written by Derek King, Architectural Historian at Preservation Studios.

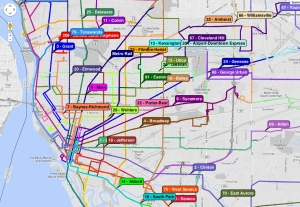

Like most cities, the perception of Buffalo's public transportation system is likely worse than using it actually is. A comprehensive bus network with several dozen routes (including express commuter lines), many routes with very frequent stops and multiple busses, and a light-rail line that could be expanded, but already features one of the greatest ridership per mile in the United States.

Unfortunately, it does suffer from a variety of problems. Up until this month, the comprehensive system was overwhelming and cumbersome. There was no "bus map" that highlighted key routes or gave times, and there were no schedules at bus stops, only the route number, and a 6-digit code representing that stop. Though most streets in the city have their own lines, allowing for incredible cross-town transportation, this means there are over 20 lines in Buffalo alone (numbered between 1 and 35), and then almost two dozen suburban lines (numbering up to 79 to Tonawanda). The numbering system for the routes can be intimidating to new riders, and confusing to people requiring several transfers.

Recently, the NFTA debuted two incredible features to help combat some of these problems. One is the system's first comprehensive map. The map allows users to browse different routes throughout the city, and directly links to printable black and white schedules that feature small route-maps as well. These black and white schedules were previously one of the only resources the NFTA offered to help riders navigate the city, which did not show connectivity or all the stops along a route. This new map helps show the broader context, and would allow riders to view times and connections between routes.

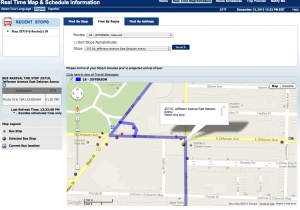

The second is far more exciting. While the online map is an important tool, it does not help riders who are away from their computer or at a bus stop and don't have any information about when the next bus might arrive. The NFTA has developed a new "Real Time" map and schedule system, that is designed to work on computers and on smart phones.

Here is how the system looks on the computer:

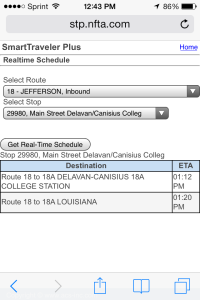

And here is the system on an iPhone:

These types of features are essential for the success of any public transportation system, but particularly in a city like Buffalo. In 2000, the US Census reported that over 30% of households in Buffalo did not own a car, and some estimate that number has only increased in the last thirteen years. With only one Light Rail line, the need for clarity on the city's bus lines is more important than ever to improve the quality of public transportation.

It should be noted, however that the 30% figure above is misleading, as it encompasses high auto-ownership areas (like North Buffalo and the Elmwood Village) and low-ownership areas like the Lower West Side and East Side neighborhoods. A 2006 study found that in highly segregated cities (like Buffalo), a disproportionate number of poorer households were not only carless themselves, but didn't even have access to a car (via neighbors or family members). The study went on to report that in Buffalo's poorest neighborhoods, the household percentage without a car was actually 47%.

Improving the quality of public transportation for the 80,000+ residents who do not have access to a vehicle should be the NFTA's top priority, and these mapping and "real time" features are a step in the right direction. Unfortunately, they are still limited to individuals with computers, internet access, or smart phones, something that is often just as out of reach as car ownership for someone living in poverty.

Indeed, the current improvements seem more in line with the NFTA's mission to increase ridership rather than improve experience. The recent Buffalo-Amherst Alternatives Study financed in 2011 is a troubling indication of the public authority's priorities, geared at attracting individuals who have and use cars toward public transportation, as well as rectifying the horrible mistake to locate UB's undergraduate campus in Getzville. Indeed, the study seems to be focused on improving public transportation options for people who prefer driving (and chose to live in auto-oriented development) as well as study something that is already pretty easy to solve (and has been discussed for over 30 years): direct and continuous access between UB's North and South Campuses.

If the NFTA truly wants to improve the experience of riders, they already know what they need to do. Their plans for Niagara Street should be implemented throughout the city, adding heated bus shelters, "next bus" clocks, and other infrastructural improvements to Buffalo's busiest bus routes. They should also be looking at ways to simplify the overly complex network, something that would benefit not only casual riders, but the increasingly large non-English speaking refugee and international community in Buffalo who rely on public transportation.

One such solution would be to create color-coded routes through-out the city, similar to the way Seoul, South Korea did, which saw bus ridership increase by 30-40%. Though the current improvements along Niagara are great first steps, a simplified map featuring some of the City's mainlines (The Metro, Grant, Niagara, Elmwood/Delaware, Jefferson, Bailey, Broadway/Genesee, Clinton/Seneca, and key cross-streets of Hertel, Amherst, Ferry, Delevan, Utica, Best/Walden) that are coded and feature the same changes as on Niagara Street could see dramatic improvement in the perception, and ridership rates, throughout the city. Better bus-to-rail service, including upgrades to the current metro-stations to better facilitate that relationship, could also improve ridership in Buffalo.

There are other options being considered as well. The Citizens for Regional Transit have outlined a comprehensive light-rail and street-car network that would dramatically improve city connectivity, not only inside Buffalo, but to regional nodes like UB and the Airport. Though ideal, there are several problems with light-rail, mainly cost-effectiveness. Not only is light-rail prohibitively expensive to construct (even using existing right-of ways, which there are plenty of in Buffalo), but the cost to run is also exorbitant. The cost to operate Buffalo's light-rail system per mile is more than double what it costs to operate a bus ($24.22/10.28 respectively), and while Buffalo's bus fare-revenue is hardly something to be proud of ($92 million to operate, $27 million in fares, or less than a third of return) the light-rail is even less impressive ($24 million to operate, $4 million in fares, or one-sixth return). Knowing that the difference in Transit Oriented Development (a measurement most urban planners use to justify expensive light-rail projects) is negligible between rail infrastructure and Bus Rapid Transit, if Buffalo is looking to expand its network on top of improving current infrastructure, bussing seems the logical way to proceed.

Really though, any improvements are welcome to this system. Slowly, Buffalo's public transportation is getting recognized (deservedly so) as a comprehensive and reliable source of transportation, and as the NFTA rolls out more infrastructure improvements (both technological and physical), its reputation will only increase. That being said, the Buffalo-Amherst study highlights the need for more targeted efforts by the region and the state to make Buffalo's public transportation better, not just broader.

In a way, that is the biggest frustration with the Buffalo-Amherst Alternatives. In trying to expand services to attract current non-users, they miss an opportunity to study what ails their system in the suburbs: it's not just Buffalo that needs better infrastructure, but Amherst as well. This stop at the intersection of Millersport and North Forest could use the same improvements currently proposed for Niagara Street:

For a number of years now, a great deal of Buffalo residents reverse-commute to areas like this, where suburban office-parks have emerged for the same reason UB selected their site in the late 1960s; cheap subsidized land. This intersection could use heated bus shelters, posted schedules, and cut-outs just as much as key corridors in Buffalo would. At least this intersection has sidewalks: one-block to the west at Jon James Audubon Parkway (which Google says is also a stop, though I can't find a corresponding route), one lonely sidewalk is the only pedestrian infrastructure for any bus riders who may be commuting to the numerous offices around the intersection.

An article on Buffalo Rising critiqued the recent stream of marketing campaigns about how nice Buffalo actually is. The author concluded, "If we want more people to know Buffalo the way we know it, we need to stop just telling people about it and simply do more of it. We need to do less of the things that’ll make “them” believe we’re something else and more of the things that’ll make them know exactly who we are."

The NFTA should take this idea to heart when considering their Amherst-Buffalo corridor and future studies in Buffalo. If they focus on improvements to change the system from something that people need to use to something people like to use, they can stop asking, "If we create new routes, will it increase ridership?"

Instead, if they make the right changes, they'll be asking, "Can we create new routes to meet ridership demands?"

Written by Derek King, an Architectural Historian in Buffalo, New York. This piece also appeared on The Buffalo Exchange.

No comments:

Post a Comment