The now abandoned elementary school

built on the south side of Martin Luther King Jr. Park was one of the first

projects I worked on at Preservation Studios.

Initially called P.S. 59 in our project folder I ran into a major issue

during my research. It appeared there were multiple P.S. 59’s and the school we

were researching, located at 787 Best Street, had once been called P.S. 24. It

was a conundrum. Which school was I researching? Why had the school morphed

from P.S. 24 to 59? In seeking the answer tot his question I dove deep into the

school’s history. In doing so I discovered first that we were in fact trying to

preserve P.S. 24 and second, we were looking at one of the most important

school buildings in Buffalo, a building whose past programs are worth recounting.

As one of the first sites for special education in Buffalo P.S. 24 carved out a

unique place in the city’s education history.

In the twenty-first century we champion

events such as the Special Olympics and binge watch a T.V show about a blind

lawyer fighting crime in Hell’s Kitchen. It’s hard to imagine our generally

accepting and inclusive attitudes towards those with physical or mental

handicaps as extraordinary. However, looking back at the tail end of the

nineteenth century it is frankly uplifting to see how far we’ve come.

Prior to 1900, most children with disabilities (both physical and mental) were treated at specialized facilities, such as the State Institution for Blind Students in Batavia, which formed in 1866.[1] In North America and Europe the prevailing belief was that mentally handicapped, blind, and deaf children were “biologically and morally inferior,” and as a result many of the earlier institutions of care and education were religiously based. [2] Handicapped students were educated in the trades because factory labor was oftentimes seen as the best employment they could gain. Children with profound mental illnesses were often times sequestered from the outside world by their own families or taken in at asylums run by the state or religious organizations. Fortunately, these attitudes began to change as child labor and mandatory school attendance laws were passed. The handicapped began to find themselves increasingly educated in schoolhouses, albeit in separate classrooms, but it was a marked improvement from the isolated vocationally and religious focused education they’d been receiving in asylums throughout the country.

Prior to 1900, most children with disabilities (both physical and mental) were treated at specialized facilities, such as the State Institution for Blind Students in Batavia, which formed in 1866.[1] In North America and Europe the prevailing belief was that mentally handicapped, blind, and deaf children were “biologically and morally inferior,” and as a result many of the earlier institutions of care and education were religiously based. [2] Handicapped students were educated in the trades because factory labor was oftentimes seen as the best employment they could gain. Children with profound mental illnesses were often times sequestered from the outside world by their own families or taken in at asylums run by the state or religious organizations. Fortunately, these attitudes began to change as child labor and mandatory school attendance laws were passed. The handicapped began to find themselves increasingly educated in schoolhouses, albeit in separate classrooms, but it was a marked improvement from the isolated vocationally and religious focused education they’d been receiving in asylums throughout the country.

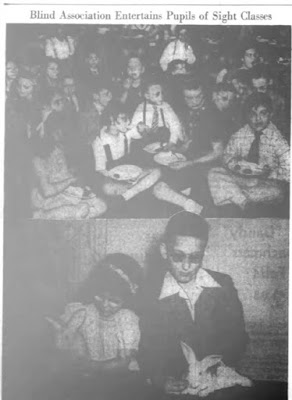

In Buffalo, P.S. 24 took the lead in

first educating the visually impaired and later became one of the earliest

training centers for children and young adults with severe learning

disabilities. Through our research we discovered that P.S. 24 was the local

headquarters of sight-saving classes in the Buffalo school district. Students

would do oral exercises with their classmates, before

heading to special courses where reading and writing would be taught with

larger fonts and bigger writing implements. The school even offered Braille

classes for high school students.[3] By

the 1940s students were being bussed from around Buffalo to attend

sight-saving, and braille classes in P.S. 24.

Where once children were isolated and

educated to become productive workers rather, by the 1940s people had revolted

against the idea that blind and deaf children were profoundly different, i.e. ineducable and morally deficient. In studying the evolution of education for

the physically handicapped it was fascinating to see the evolution of American

education practices. At the start of classroom integration it seemed that

visually impaired students finding success in the classroom was greeted with

pleasant surprise. The transition would be much slower for students with mental

handicaps, however once again it would be at P.S. 24 leading the way in

education for the profoundly mentally handicapped children.

Stay tuned for Part II…

|

| Image courtesy of Fultonhistory.com |

[1]

Margret A. Winzer, The History of Special

Education From Isolation to Integration (Washington D.C.: Gallaudet

University Press, 1993), 317.

[2]

Winzer, 171.

[3]

“Sight-Saving Classes for School are Given Praise by Group,” Buffalo Courier-Express, February 22,

1934, 11. Accessed 7/1/15 via FultonHistory.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment