By Matthew Shoen

St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York is a small private

liberal arts college that recently found its way onto Best College Reviews list of the top 50 Historically Notable

Colleges in America. St. Lawrence also happens to be where Derek and I went to

school so now seems like a good opportunity to shamelessly plug the university

and look at its early years.

For people who've attended St. Lawrence the basics of its history are

commonly retold. The university was founded in 1856 as a theological school by the Universalist Church and became the first coeducational institute of higher learning in New York State. The Universalists who

founded St. Lawrence believed that the illimitable love and goodness of God

would triumph over evil in human society, and that God, irrespective of religious creed was a force of love in human life.[1]

Less concerned with theological differences and proper religious practices, the Universalists were eager to create a theological school to promote their views.

Leaders among the Universalist community, whose members primarily came from New England, Western New York and the Finger Lakes Region eventually decided to build their

university in Canton, a small town in St. Lawrence County. Those members of the

congregation in favor of Canton argued that they had found, “a site

of twenty acres of good available land, centrally and beautifully located on a

gentle eminence.”[2]

The construction of what would become Richardson Hall, St. Lawrence’s first

building, started in 1855 and in the course of its construction the citizens of

Canton convinced the Universalists to expand the scope of their theological

school to include a college of Letters and Science forming the base of the

liberal arts education for which St. Lawrence is known.

The early years of St. Lawrence were difficult and the university

nearly went under as it struggled to attract students and faculty to the remote

North Country. Still the university managed to provide for its

students and built out the campus starting with the Herring Library in 1869 and

the Fisher Theological School in 1883. The addition of the Cole Reading Room in

1902 gave Herring-Cole its present form and marked the end of St. Lawrence’s challenging

first phase of development.[3]

|

| Image of Richardson Hall and the Herring Library taken from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Richardson Hall. |

Where the nineteenth century

had been challenging to St. Lawrence University’s Universalist founders, the

opening decades of the twentieth century were far kinder. Between 1904 and 1911

the university was able to build many of the academic buildings that hold classes

and offices today. These buildings include Carnegie, Cook, Payson, and Memorial

Hall. Carnegie Hall became the university’s first science building after a

donation of laboratory equipment from A. Barton Hepburn, a North Country native

who became one of St. Lawrence University’s greatest patrons.[4]

The ability to hold science classes in Carnegie allowed the university to

convert Richardson Hall into a lecture space dedicated to the humanities. In

addition to private donors such as Hepburn, the 1910s saw New York State involve itself in

St. Lawrence’s affairs paying for the construction of Cook and Payson Halls to

serve as the first State School of Agriculture.[5]

The state would purchase a 63-acre farm and use the farm and new academic

buildings to house dairy laboratories, horticultural devices, and plantings.

St. Lawrence would later purchase both Payson and Cook Halls and the

agricultural school would become SUNY Canton starting in the 1960s.

With its finances growing

increasingly secure and with endowments coming from numerous sources St.

Lawrence cemented itself as a top flight university in 1929 with the dedication of Hepburn Hall where

Marie Curie the two time Nobel Prize winning physicist and chemist and pioneer of

radiation research spoke. Curie was convinced to inaugurate the opening of Hepburn

Hall by Owen D. Young, university trustee and internationally known financier.

In addition to convincing Curie to come to Canton, Young was the mastermind

behind the construction of St. Lawrence’s Gunnison Memorial Chapel, Sykes

Residence for Men, and Dean Eaten Hall.[6]

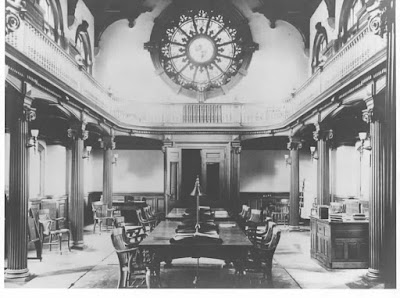

|

| Historic Image of Herring-Cole Taken from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for the Library |

With the building of Dean Eaton

Hall and Sykes Residence the shape of St. Lawrence was effectively finalized.

Expansion of the campus would continue as the university sought more students

and a more diverse curriculum, but every building that came after the completion

of Sykes in 1930 reflected the types of buildings already built, i.e.

residences, libraries, common spaces, and academic halls. The university’s

historic core, expressed in buildings such as Herring-Cole, Sykes Residence, Richardson, Carnegie, and Hepburn Halls trace the

fascinating story of St. Lawrence’s first eighty years of existence. From a single brick

building on the edge of Canton to a thriving liberal arts college hosting

internationally renowned guests like Marie Curie the story of St. Lawrence is

one of triumph. Importantly though, it is not the story of triumph over

overwhelming odds or adversity, instead it is a triumph of ideals, a triumph of

education and a triumph of a belief fostered by people ranging from the

citizens of Canton who asked the Universalists to expand the mission of their

college, to financiers like A. Barton Hepburn and Owen D. Young that knew

education in this quiet part of New York could be something special.

|

| Marie Curie Comes to Dedicate Hepburn Hall October 26, 1929 Taken from St. Lawrence University's Digital Collection |

For additional information on the history of St. Lawrence University consider following these links:

http://www.bestcollegereviews.org/features/historically-notable-colleges/

https://cris.parks.ny.gov/Uploads/ViewDoc.aspx?mode=A&id=32513&q=false

https://cris.parks.ny.gov/Uploads/ViewDoc.aspx?mode=A&id=32510&q=false

https://cris.parks.ny.gov/Uploads/ViewDoc.aspx?mode=A&id=32411&q=false

[1] Cornelia E. Brooke,

“National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Richardson Hall, 1974.”

Section 8, Page 1.

[2] Brooke, “Richardson

Hall,” Section 8, Page 1.

[3] Sadly Fisher Hall

burned down in 1951. The building of Herring Cole continued the pattern of

unity between St. Lawrence University and the local community as Potsdam

Sandstone, a locally and widely sought building material was used to erect the

building.

[4] Hepburn, president of

Chase National Bank from 1904-1917 also endowed the university with the money necessary

to begin an Economics program

[5] John Harwood, “National

Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: St. Lawrence University Old Campus

Historic District, 1981” Section 8, Page 1.

[6] St. Lawrence students

will find amazing is that Dean Eaton is actually considered historically

significant.

No comments:

Post a Comment